If people know the name Joel Roberts Poinsett today, it is likely because of the red and green poinsettia plant.

In the late 1820s, while serving as the first ambassador from the U.S. to Mexico, Poinsett clipped samples of the plant known in Spanish as the “flor de nochebuena,” or flower of Christmas Eve, from the Mexican state of Guerrero. He then introduced it to the U.S. on a trip home from Mexico.

The plant has been named poinsettia ever since.

But much like the history of the U.S., Poinsett had a complex and troubling past.

An ambitious politician, financial investor and enslaver, Poinsett was a secret agent for the U.S. government in South America who fought for the Chilean army against Spain during Chile’s War for Independence in the early 1800s.

A confidant of President Andrew Jackson, Poinsett also served as U.S. secretary of war under President Martin Van Buren and oversaw the ignominy of the Trail of Tears, the forced relocation and deadly march of Cherokee people from the South to reservations in the West during the 1830s.

And yet Poinsett, an avid botanist who brought scores of other plants to the U.S., also helped found an organization that led to the creation of the Smithsonian Institution.

A privileged life

I came across his history almost by accident. I am a historian of capitalism in early America, and while I was on a research fellowship for my first book, “Manufacturing Advantage: War, the State, and the Origins of American Industry,” another researcher suggested I go to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania to check out the papers of a few War Department officials. Poinsett was one of those officials.

There, I found a large collection of his letters and other personal papers that spanned five decades of his life. I became so fascinated with his life that I decided to write a book about him. I detail his complicated life in another book, “Flowers, Guns, and Money: Joel Roberts Poinsett and the Paradoxes of American Patriotism.”

Born and raised in Charleston, South Carolina, on March 2, 1779, Poinsett was the son of a wealthy doctor and lived a life of privilege. He traveled throughout Europe and Russia in his early 20s before starting a military career.

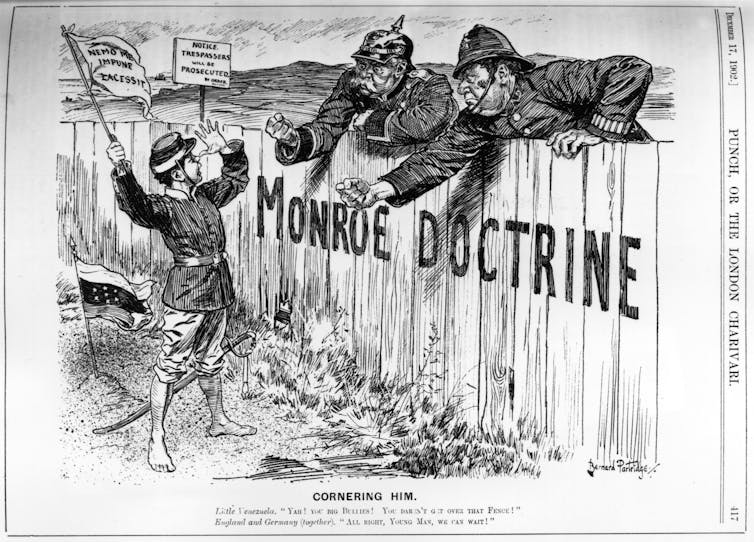

In the 1810s, Poinsett traveled around South America as a secret agent of the U.S. State Department. His intelligence reports led in part to the drafting of the Monroe Doctrine.

That doctrine, written by Secretary of State John Adams and buried in President James Monroe’s address to Congress on Dec. 2, 1823, sought to prevent European colonization in South America and, in essence, claimed the entire Western Hemisphere for the U.S.

The doctrine also set the stage for two centuries of rocky relations between the U.S and Latin America.

In 1825, the Monroe administration appointed Poinsett as the nation’s first ambassador to Mexico. He arrived there in the spring of that year and almost immediately instigated a general distrust of American interference. He used his connections to secure favorable plots of land for himself and his friends and established a U.S.-based mining company to exploit Mexican resources for his own benefit.

It was on a trip to assess the profitability of some mines, in fact, that Poinsett admired the red and green plant and cut clippings to send to horticulturalists in the U.S. Exactly where and how these clippings were made and sent is not quite clear, but he remarked on the beauty of the plants he saw, which Franciscan friars in Mexico had been displaying at Christmas since the 1600s.

Several prominent horticulturalists in the United States later reported that Poinsett sent them plant samples. By the mid-1830s, agricultural reports described a plant with brilliant scarlet foliage, “lately referred to as the poinsettia,” as having been introduced by Poinsett in 1828.

Poinsett’s Latin America meddling

That same year, Poinsett also supported a coup in Mexico City.

During the Mexican presidential campaign in 1829, Poinsett supported Vicente Guerrero, whom he saw as more amenable to his and U.S. financial interests. When Guerrero lost to moderate Manuel Gómez Pedraza, Guerrero staged a coup with Poinsett’s approval that forced Gómez Pedraza to flee Mexico.

Because of Poinsett’s poor conduct during the election, the Mexican government requested Poinsett’s removal from his post. President Andrew Jackson instead allowed Poinsett to resign.

Poinsett left Mexico and went back home to South Carolina.

On Oct. 24, 1833, at 54 years old, Poinsett married a 52-year-old, wealthy widow from South Carolina who owned a rice plantation and almost 100 enslaved people.

Though he wrote that he enjoyed married plantation life, he was not done with politics or the military.

In 1837, Poinsett was named U.S. secretary of war and oversaw the execution of Jackson’s 1830 Indian Removal Act that the Cherokee people referred to as the Trail of Tears. That act saw the violent displacement of members of the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw and Choctaw nations from their homelands in the South to reservations in the West.

The creation of the Smithsonian

Based on his travels and experiences around the world, Poinsett believed that the U.S. should have a national museum to conduct scientific research and display the expanding government collections, including plant specimens.

In his retirement, Poinsett helped found in 1840 and became president of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science and the Useful Arts.

That organization later became part of the Smithsonian Institution, whose gardens now showcase thousands of poinsettias during the Christmas season.

Poinsett died on Dec. 12, 1851.

It remains unclear how long the plant that bears his name will remain known as the poinsettia. After years of controversy, the American Ornithological Society announced that it was going to remove all human names from as many as 152 bird species, including those linked to people with racist histories or people who have done violence to Indigenous communities.

Though no attempts as yet have emerged to rename plants, it’s my belief that Poinsett’s poinsettia may be the first.

Lindsay Schakenbach Regele, Assistant Professor of History, Miami University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.